_

_

The Jewish communities have offered to convert these immigrants. However, many contingency-refugees, such as Diana, told EJP that they do not think it is right for them to have to convert to something that they feel that they already are.

_

Over the last 15 years more than 200,000 Jews have immigrated to Germany from the former Soviet Union (CIS).

_

Recent statistics compiled on behalf of the German government show that 205,905 Jews came from the CIS to Germany between 1991 and 2005. The largest influx of arrived between 1995 and 2004, when an estimated 10,000 Jews per year entered Germany as permanent residents.

Recent statistics compiled on behalf of the German government show that 205,905 Jews came from the CIS to Germany between 1991 and 2005. The largest influx of arrived between 1995 and 2004, when an estimated 10,000 Jews per year entered Germany as permanent residents.

_

Many of the Jews were driven out of the CIS after an upsurge in anti-Semitism. When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, Soviet Jews feared an increase in anti-Semitic violence. And indeed, anti-Semitic violence and hate propaganda surged when newly-founded right-wing parties and nationalist groups took advantage of the political freedoms that resulted with the demise of communist party hegemony. In the early 90s, most Jews left with the pretext that the newly founded Russian Federation was becoming increasingly dangerous for Jews and other minorities.

_Many of the Jews were driven out of the CIS after an upsurge in anti-Semitism. When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, Soviet Jews feared an increase in anti-Semitic violence. And indeed, anti-Semitic violence and hate propaganda surged when newly-founded right-wing parties and nationalist groups took advantage of the political freedoms that resulted with the demise of communist party hegemony. In the early 90s, most Jews left with the pretext that the newly founded Russian Federation was becoming increasingly dangerous for Jews and other minorities.

Until January 2005, Jews from the former Soviet Union could enter Germany as contingency refugees. This status allowed Jews to be able to get around Germany’s ever-increasing immigration restrictions. The contingency-refugee law, passed on January 9 1991, did not limit the number of Jews that could enter Germany. It was also an open-ended law – meaning that there were no time restrictions forcing Jews to make the decision of whether or not to emigrate or when.

_The German government has recognised that a great many immigrants from the former Soviet Union have been seeking to establish residency in Germany for the sole purpose of bettering their economic standing or in order not to lose their chance at being allowed to receive automatic residency.

_Nonetheless, the government has exercised restraint over the past 15 years. Knowing that it had a historical debt to pay to the Jews of Europe, it sought to right a historical wrong by supporting the re-population of former Jewish centres throughout Germany through its Jewish immigration policy. However, the government has come under increasing pressure to revamp its failed integration policies.

_But even the cash strapped Jewish communities want to see more involvement in their congregations by the new immigrants, should they seek to live in Germany – and have thus found a consensus with immigration policy makers. “If the immigrants do not want actively participate in Jewish life here, then what on earth are they coming here for… they might as well stay home” one disgruntled Berlin community member told EJP.

_The member lamented that at least half of all CIS Jews have not registered with a local congregation. In fact, of the 220,000 Jews living in Germany today, only 120,000 are officially registered with any congregation associated with the Central Council of Jews in Germany.

_“Many of the Russians are not members because many of them are not Jewish in the first place,” one Dresden Jewish community leader told EJP [2,3].

_She was referring to Jewish law which prescribes that a Jew is a person born of a Jewish mother. German immigration policy, however, has also let the offspring of Jewish fathers into Germany as contingency-refugees.

_“Anyone descended from a Jew, whether from a Jewish mother or, only, a Jewish father was considered ethnically Jewish in the former Soviet Union. Anyone there that was branded ‘Jewish’ was open game to all forms of discrimination. Therefore, the German government did not distinguish between a people whose mother or only whose father was Jewish,” an interior ministry source said.

_This policy has, however, also created a social problem among the contingency-refugees within Germany’s established Jewish community structures.

_Many of these so-called not-Jewish-Jews are not considered Jewish by their local congregations, even though they have shown an interest in becoming a member of a congregation.

_“In Russia, I was discriminated for being a Jew. In Germany, the Jewish community does not let me become a member because my mother was not Jewish,” Diana K., a Ukrainian immigrant to Berlin told EJP.

_“If being Jewish is a heritage, then it must also come from the father,” Diana said.

_

_

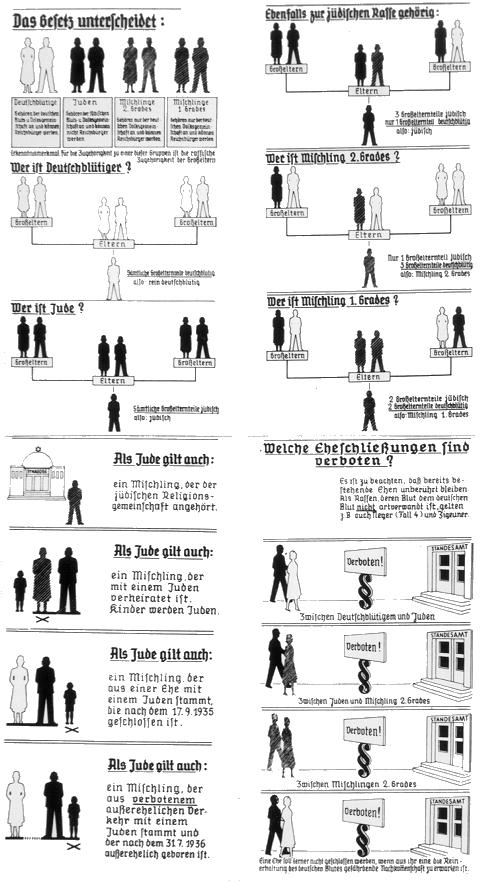

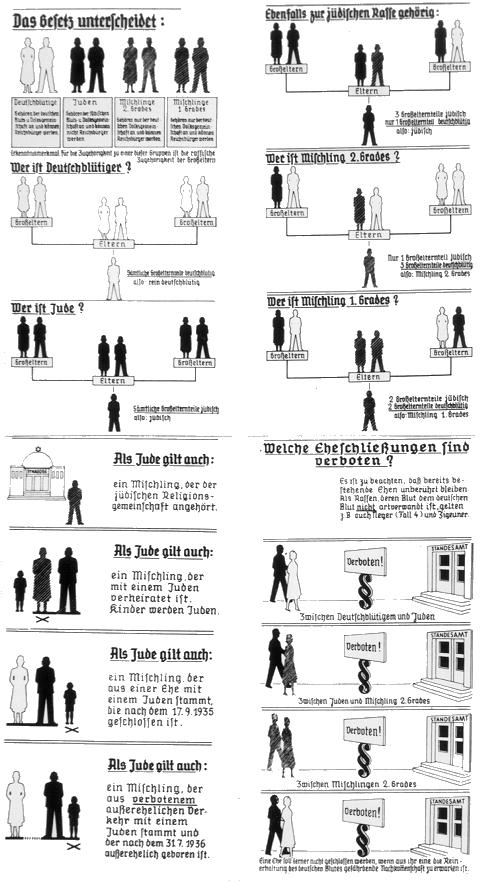

Nuremberg Race Laws [4]

_The Jewish communities have offered to convert these immigrants. However, many contingency-refugees, such as Diana, told EJP that they do not think it is right for them to have to convert to something that they feel that they already are.

_

Like in Israel, many Russians who have immigrated here are neither Jewish from either their mother or father’s side. Some are the spouses of Jews. However, many have used falsified documents claiming to be Jews for the sole purpose of obtaining easy visa for a western country.

_Since last year, the Jewish roots of new immigrants are being more severely scrutinised at German consulates throughout the CIS.

_As a result of the tightening up of the contingency-refugee laws, which also makes it mandatory for new arrivals to become active members of a Jewish synagogue congregations, fewer Jewish immigrants have been coming into Germany.

_Last year, less than 6,000 Jews entered Germany from CIS countries. So far this year, fewer than 400 Jews have immigrated to Germany. Non-Jewish spouses and children will still be let into Germany, as long as the Jewish partner fulfils the new requirements.

_Perhaps due to Germany’s historical responsibility towards Jews, government analysts have avoided scrutinising the integration processes of the contingency-refugees. Thus, official statistics about the integration of Jews is not available.

_One source told EJP that most offspring of CIS-Jewish immigrants have learned German and, unlike immigrants from most other non-EU countries, an above average number of them have gone on to further their education. However, many of their parents cannot speak German properly and have been collecting some form of state aid. Also, many have been unwilling to identify with Germany at all. In fact, many have shown open disdain for their host country as a result of its Nazi past.

_At a leadership conference of Germany’s Jewish Student Union, last year, the question of whether the Union should better integrate itself with other student organisations was rejected. Most of the student leaders underlined the fact that Jews were still not being accepted by other groups as full-fledged citizens and thus they did not feel that any alliance with other student or civic organisations would further their cause.

_Because of their claim that Germany is severely riddled in latent anti-Semitism, about half of the student leaders even claimed that they were still in Germany only because of their parents and that Germany was nothing more than a way-station for them on their final road to Israel or countries with a less tainted past.

_

"Such an attitude is not indicative of whether a person is integrated or not,” the interior ministry source said. “If the immigrants learn the language, have a job and have a clean police record, then they are considered integrated,” he said. “Since about half of these young people’s parents have no solid working knowledge of German and because a large number of these hold no long-term job, then we can assume that the integration process has failed here too.”

"Such an attitude is not indicative of whether a person is integrated or not,” the interior ministry source said. “If the immigrants learn the language, have a job and have a clean police record, then they are considered integrated,” he said. “Since about half of these young people’s parents have no solid working knowledge of German and because a large number of these hold no long-term job, then we can assume that the integration process has failed here too.”

__

In order to combat language and social deficits among its migrant population, the government has intensified its offer of German and integration courses – free of charge. Such courses are now mandatory for recipients of welfare benefits. For many Jews from the CIS, these courses have been made available at Jewish community centres throughout Germany.

_

However, as one critic put it, “how do you expect these Russian speaking Jews to properly learn German or to integrate with other cultures in Germany if their courses are held among themselves… this is indicative of why integration has been failing”.

However, as one critic put it, “how do you expect these Russian speaking Jews to properly learn German or to integrate with other cultures in Germany if their courses are held among themselves… this is indicative of why integration has been failing”.